Researching the Geography of Transition

Dr Giuseppe Feola, University of Reading

www.giuseppefeola.net g.feola@reading.ac.uk October 2017 I have been interested in grassroots sustainability movements for a long time, and have studied the voluntary simplicity movement and solidarity purchasing groups in Italy, and the Transition Towns Network internationally. In the past few years I have been especially curious about the geography of the Transition Network. These were some of the questions that guided my research: why do grassroots-led transitions to sustainability occur in one place and not in another? How do place, space and scale influence these processes of transition? How do such grassroots sustainability movements re-make places and spaces both symbolically and materially? Can we learn anything useful for grassroots sustainability movements by uncovering their spatial patterns of diffusion? |

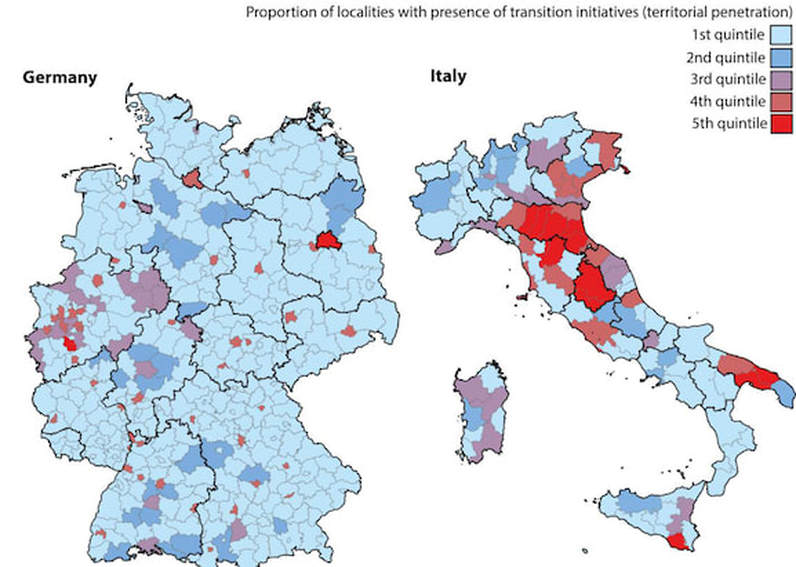

I believe one of the most interesting findings of my research to date is that the Transition Network does not diffuse everywhere. We know that the Transition Network has spread in just a few years from Britain to many countries worldwide. This rapid spread of Transition in many different contexts has been talked about by some observers in terms of a ‘viral’ diffusion. This narrative tends to imply, explicitly or more subtly, that Transition could happen—in fact, that it is already happening—everywhere! This is a positive and powerful narrative that can motivate others to embrace Transition. However my research has shown that the Transition Network is characterized by clear spatial patterns: geographical location matters with regard to both where transition initiatives take root and the extent of their success. First the Transition Network has not spread equally everywhere and I have identified ‘hotspots’ of Transition (places where Transition Initiatives have emerged more densely). Second place-specific factors contribute to determining the likelihood of a transition initiative existing in the long term and bringing about desired change locally. Transition Initiatives remain largely determined by place-specific processes despite their interdependence with a trans-local network like Transition Network.

What does this mean for Transition? Does it mean that Transition is necessarily bound to fail in certain places? Not really. Far from implying a resizing of the potential of Transition, these findings suggest that Transitioners should be perhaps more aware of the preconditions that may favour grassroots movements in particular places, and of the possible barriers that local initiatives may encounter in other places. By being more aware of these place-specific conditions and barriers, both international and national hubs and local initiatives can be more prepared while also attempting to influence those contextual conditions (for example: local coalitions). In sum the Transition Network is not an unstoppable ‘viral’ wave that is sweeping any place, but to realize this can be good: by understanding where Transition does well and where it does not, we can help it adapt to different contexts, that is to be prepared to seize place-specific opportunities and avoid equally place-specific challenges. This research has had resonance in some Transition discussion groups online and has been used by transition training programmes.

Another interesting aspect of this research is that I have used methods that are uncommon in Transition research. Most studies of Transition have employed qualitative methods (e.g. participant observation, in-depth interviews) in one or a very limited number of case studies. This type of research in helpful in gaining insight into specific cases, but is not appropriate to know whether those insights apply to other cases as well, that is whether the lessons learned from one or a few cases can be generalized to other cases. Moreover, when focussing on only one case study, we cannot appreciate differences between contexts, and therefore it is more difficult to appreciate the importance of place, space and scale in the emergence and development of Transition Initiatives. The methods that I have used, instead, were a quantitative survey and spatial statistics. Through these methods I have been able to identify general patterns of spatial diffusion and of success and failure. This knowledge complements qualitative in-depth studies of individual transition initiatives.

Various people have accompanied me in this research. Beside the many Transitioners who have kindly participated in my survey, Richard Nunes (University of Reading) has been invaluable and inspiring collaborator. Various students, particularly Anisa Butt and Mina R. Him, have also been important in conducting this work. I am currently co-supervising a doctoral student (Emily Nicolosi, University of Utah) who is further developing some of these ideas in her study of grassroots innovations for sustainability in the United States of America.

Most of the findings of my research on the geography of Transition to date are published in four articles that can be freely downloaded or requested at the following links:

Another interesting aspect of this research is that I have used methods that are uncommon in Transition research. Most studies of Transition have employed qualitative methods (e.g. participant observation, in-depth interviews) in one or a very limited number of case studies. This type of research in helpful in gaining insight into specific cases, but is not appropriate to know whether those insights apply to other cases as well, that is whether the lessons learned from one or a few cases can be generalized to other cases. Moreover, when focussing on only one case study, we cannot appreciate differences between contexts, and therefore it is more difficult to appreciate the importance of place, space and scale in the emergence and development of Transition Initiatives. The methods that I have used, instead, were a quantitative survey and spatial statistics. Through these methods I have been able to identify general patterns of spatial diffusion and of success and failure. This knowledge complements qualitative in-depth studies of individual transition initiatives.

Various people have accompanied me in this research. Beside the many Transitioners who have kindly participated in my survey, Richard Nunes (University of Reading) has been invaluable and inspiring collaborator. Various students, particularly Anisa Butt and Mina R. Him, have also been important in conducting this work. I am currently co-supervising a doctoral student (Emily Nicolosi, University of Utah) who is further developing some of these ideas in her study of grassroots innovations for sustainability in the United States of America.

Most of the findings of my research on the geography of Transition to date are published in four articles that can be freely downloaded or requested at the following links:

- Feola, G., Nunes, J.R. 2014. Success and failure of Grassroots Innovations for addressing climate change: the case of the Transition Movement. Global Environmental Change, 24:232-250. [Open access here]

- Feola, G., Him, M.R. 2016. The diffusion of the Transition Network in four European countries. Environment and Planning A, 48(11):2112-2115. [Open access here]

- Nicolosi, E., Feola, G. 2016. Transition in Place: Dynamics, Possibilities, and Constraints. Geoforum, 76:153-163. [Open access here]

- Feola, G., Butt, A. 2017. The diffusion of grassroots innovations for sustainability in Italy and Great Britain: an exploratory spatial data analysis. Geographical Journal, 183(1): 16-33. [Open access here]